December 27, 2015: “Rock ‘n’ Roll High School Writer Joseph McBride Discusses The Ramones’ Classic, New Memoir”

Interview/Review by Bob Wilson, LiveForLiveMusic.com.

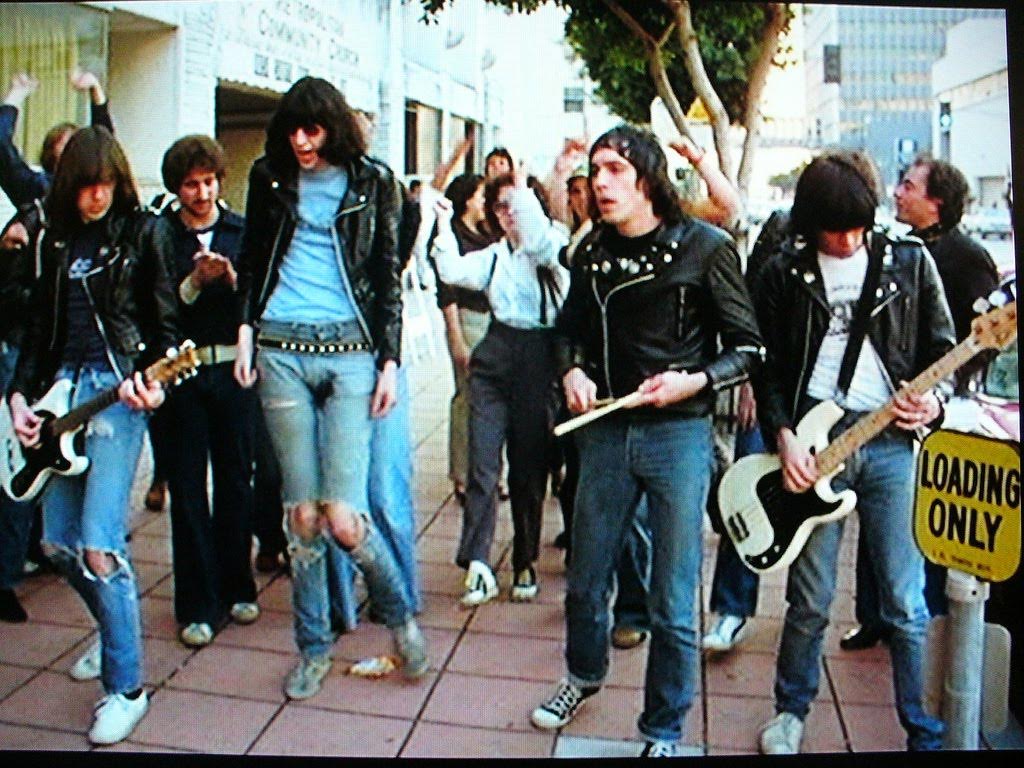

The Ramones were the archetype for most every punk rock band that came after, from The Sex Pistols to The Clash. In 1979, the group took the route of The Beatles and starred in a musical film: Roger Corman’s Rock ‘n’ Roll High School. Corman was “The Pope of Pop Cinema,” intending for this new film to be a modern version of his popular teen films from the 1950’s.

The script was co-written by Joseph McBride, based on an incident that had happened to his own father in the 1920s. McBride’s father, Raymond McBride, was a reporter for the Milwaukee Journal, and had led a student strike at Superior Central High School in Wisconsin in his youth.

The film was constructed over a bedrock soundtrack featuring the Ramones, Paul McCartney, Lou Reed, Alice Cooper, Chuck Berry and others. The music alone was likely to garner attention, along with an appearance by the up-and-coming Ramones. The plot features P. J. Soles as Riff Randell, a rebellious teen anxious to meet Joey Ramone so she can show him the efforts of her songwriting. Riff has had “more detentions than anyone in the school’s history” and is the prototypical rebel with a mission.

The musical romp would go on to legendary status as a “midnight B cult movie” that would have a perpetual niche among rock fans. Unnoticed on the surface was that the rebellion in the film was based upon the real-life experiences of Joseph McBride in his youth. While attending a strict Catholic high school, Marquette University High School in Milwaukee, McBride won a National Merit Scholarship but had to be institutionalized for a time, succumbing to the church’s pressures over adolescent sexual urges and the self-imposed pressures of aspiring to win admittance to Harvard. McBride also experienced the worst of Draconian discipline that went with a strict Catholic education. His experiences can be found in his astonishingly honest new book, The Broken Places: A Memoir (Hightower Press, 2015).

On the surface, the music of the Ramones seems penned by sheer comic genius, turning topics such as shock treatment and Thorazine into humorous spoofs. On closer inspection, the Ramones’ inspiration was also much darker than the surface would lead one to suspect.

Joey Ramone suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia (and passed away in 2001 of lymphoma). Bassist Dee Dee Ramone had his own ills, as he battled bipolar disorder and drug addiction. Dee Dee would succumb to a heroin overdose in 2002. Given the history of the band, it is harder to laugh at songs such as “Teenage Lobotomy,” “I Wanna Be Sedated,” and “We’re a Happy Family.”

The theme McBride expounds upon in his new memoir The Broken Places touches on similar issues as those that plagued the band. As you re-watch Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, it is fascinating to consider the experiences that both the writer and the band lived through. The ending of the film features the kids blowing up their high school, a startlingly realistic-looking scene shot (on a low budget) at the shuttered Mount Carmel High School in the Watts section of Los Angeles.

Joseph McBride’s tale is as fascinating as The Ramones’. McBride endured Catholic school educators who hit students with a sawed-off golf club and spewed acidic verbal emotional abuse. In third grade, her teacher gave rulers to McBride’s female classmates to beat him over the head as they saw fit. Later, the nun would be sent either to a home for disturbed nuns or a mental institution. The educator would leave a great deal of emotional damage in her wake to the youth she was entrusted to teach. Constant bullying and the pressures of being a perfectionist student would lead McBride eventually to a breakdown.

In treatment, McBride would meet Kathy Wolf, a Riff Randell-like rebel that he would credit with saving him from his miseries. In a story as romantically touching and tragic as anything else offered in literature, the half-Menominee Native American would later become a victim of suicide. Her own story is beyond mere heart-wrenching, and etches itself onto the reader’s soul and memory.

L4LM’s Bob Wilson sat down with Joseph McBride, to discuss the Ramones, his life experiences, and his new memoir, The Broken Places.

L4LM: Why is the medium of film so important to you?

Joseph McBride: Films question moral teachings, and that helped lead me to always being a film buff. I had my horizons expanded as a youth by such films as Dr. Strangelove, The Diary of Anne Frank, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Lawrence of Arabia, and Some Like It Hot. The church had the annual pledge for the Legion of Decency, and when we were supposed to take the pledge at Mass in the late summer of 1965, I remained seated while the rest of the congregation was standing. That made my father very angry and was my first form of expressing overt rebellion against the church. It took me until 1967 to break with Catholicism for good; leaving the church and leaving the film industry were the two best decisions I ever made, and the two most difficult. Without those steps I wouldn’t be here today.

L4LM: School was a torturous experience for you. Can you tell us a bit about that?

JM: Catholic schooling in that era (1953-65) was a very repressive atmosphere in many ways, both physically and psychologically. Marquette was a strict Jesuit high school in Milwaukee, and the disciplinarian, Father Boyle, would whip us for infractions of discipline with a sawed-off golf club. The education I received there was first-rate in many ways, but the brainwashing and intimidation were damaging. But I had it far worse at St. Bernard’s Grade School in Wauwatosa, especially with the psychotic Sister Magdalena during the year she spent abusing me with the help of many of my fellow third-grade students.

L4LM: How did you come to be involved in writing Rock ‘n’ Roll High School with the Ramones?

JM: The first draft of the script was dictated by Joe Dante and Alan Arkush into a tape recorder so Roger Corman could save money by hiring a Writers Guild of America member (i.e., me) to “rewrite” it at the half-price rewrite fee. Their “script” came to sixty pages when typed and was pretty much a mess; it didn’t have a plot. I was hired to come up with a plot and was inspired by one element in their script, when a pet monkey takes drugs the students are whipping up in chemistry lab and grows to King Kong proportions, breaking through the roof of the school. That made me think of building up a story to rebellion (a natural idea for a high school movie in any case) and destruction.

A beloved female teacher had been fired at my father’s high school, and the students went out on strike for a month. The teacher was reinstated as a result. That stuck in my mind as a good springboard for a movie, but it would have been somewhat mild compared to the student demonstrations and riots of the 1960s and ‘70s when I was involved in anti-Vietnam War protests as a student at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and as a reporter for the local newspaper. I came up with the ending of Rock ’n’ Roll High School by remembering how the students in Madison had blown up the Army Mathematics Research Center in 1970, killing a graduate student. That recklessly destructive act also helped kill the antiwar movement. I combined those ideas to construct the idea for the ending of this film.

L4LM: What was it that led to your nervous breakdown in high school?

JM: I spent the second half of my senior year in the hospital, but still was allowed to graduate. I was stressed not only by excessive schoolwork and pressure to succeed and my Catholic guilt but also by home problems caused by my parents’ alcoholism. I also probably suffered from anorexia. At the mental hospital, I met Kathy Wolf, a half-Native American, half-Irish young woman. She was free-spirited and helped to get me out of my shell. We wound up dating, and our relationship freed me from many of my Catholic inhibitions. She was diagnosed as schizophrenic and wound up committing suicide years later. I was getting better, but she was getting worse. That’s the poignancy of the story I tell in The Broken Places.

L4LM: When did you get the idea to tell this story in book form?

JM: In 1967, I started writing the story as Holy Joe. It was a facetious draft about my issues involving Catholicism. But I realized it was too flippant for the subject matter, so I went back to it later with more perspective and worked on it over a long period of time. It turned into a memoir, which I wrote with no holds barred. Tennessee Williams said a writer should never be embarrassed, which inspired me during the many tough times writing it. It was a cathartic experience, which is one reason I wrote it. The other was to pay tribute to Kathy and bring her back to life in the only way I could.

L4LM: You co-wrote (with Richard Whitley and Russ Dvonch) and appeared in Rock ‘n’ Roll High School. What comes to mind when you remember that experience?

JM: One important point about the movie is that the girls are the leads. That was extremely unusual for the seventies, when most Hollywood movies were buddy-buddy movies, and there were few good parts for women. I decided to reverse that by making this a female buddy-buddy movie. Hardly anyone commented on that radical step we took. It just worked well, and the two actresses (P. J. Soles and Dey Young) are excellent.

L4LM: Kathy Wolf seems somewhat of a model for the movie’s Riff Randell character.

JM: Yes, indeed. I modeled the Riff Randell character on Kathy. They share the same rebellious and life-enhancing spirit, although fortunately Riff is not mentally ill. The other female character, the more intellectual science genius Kate Rambeau, I modeled on a later girlfriend of mine, Laurel Gilbert, who was more sedate but also very bright and appealing. Riff and Kate make a good complementary pair. When you write a screenplay, you can work in covert personal dimensions as long as you don’t let on to the director about what you’re doing. The male lead, Tom, the square Vince Lombardi High School quarterback played by Vince Van Patten, I modeled somewhat on our star quarterback at Marquette, Tom Fox; Kate calls Tom a “fox.”

L4LM: Did the script evolve along the way?

JM: Yes, I did five drafts, working with director Allan Arkush and Corman’s brilliant story editor, Frances Doel. I created the plot and the characters. Then the other two writers were brought in to do a rewrite, because Arkush wanted the film to be “more zany.” They added Clint Howard as Eaglebauer, the school macher, who was based on the classic TV character, Sergeant Bilko. I very much enjoy the comical sex lesson Eaglebauer gives to Kate and Tom.

The other writers also rewrote the dialogue. I write much better dialogue than that. There’s a lot of juvenile humor in the final script, along with lines pilfered from Bob Hope and Woody Allen movies. But it plays well anyway. Allan Arkush brought tremendous energy to his direction. I think what makes the film endure is that underneath all the wild antics is a serious political dimension about repression and rebellion. We dealt with nihilistic violence in a satirical way. The one bit I regret they added was the disc jockey Screamin’ Steve saying at the end of the film, as the school burns, that if you want this to happen at your school, give ol’ Screamin’ Steve a call. I think the other writers and the director missed the point of blowing up the school. I wanted to satirize how a legitimate revolution can easily turn nihilistic. They seemed to think we were simply celebrating it.

Joey Ramone and Director Allan Arkush on the set of Rock N Roll High School (1979)

L4LM: Was blowing up the school your idea for the ending?

JM: Yes, and Arkush initially opposed the idea, saying it would “make the students unsympathetic.” But I thought of a way to manipulate him [laughs]. I tricked him into doing the scene by doing what I recommend to my screenwriting students, that they “mind-f*ck” the directors. I mentioned to Allan that Jonathan Kaplan had delinquents burn down their recreation center in a movie that was then filming, Over the Edge, made by Orion Pictures. Kaplan was an alumnus of Corman’s New World Pictures, and directors at New World were always terribly envious of anyone who had moved on to bigger things. So I said to Allan that we had to top Kaplan by blowing up the school, and Allan got all excited. Roger Corman loved the ending; he later said it was the main reason he agreed to make the movie. Allan later claimed he dreamed up the ending while he was attending high school, but I was pleased when he finally acknowledged in a recent interview that I had suggested it.

L4LM: How did the Ramones come to star in the film?

JM: The budget for the film was only $280,000. We made amazing deals to be able to use forty-five songs, including one by Paul McCartney and Wings that was written for and rejected by Warren Beatty’s Heaven Can Wait; we got it for only $500. The Ramones accepted $25,000 for the entire group to appear in the movie. The Ramones were Roger Corman fans and felt that this would be their ticket to stardom. They were not a mainstream band, and they wanted to move beyond their niche.

L4LM: The Ramones are a cult classic group, but never really made the mainstream, did they?

JM: Phil Spector came in after that and changed their outfits, dressing them in pastel colors. Spector had them cut their hair and tried to change their image from leather-clad punks to mainstream rockers. That was a disaster, so they went back to their old image. They never crossed into the mainstream or made another film except for appearing in documentaries. They were so out there that they could never have been mainstream; that’s their glory. Songs about child abuse and glue-sniffing weren’t played much on the radio. But the Ramones tapped into the true youth culture and continue to capture much about the twisted nature of growing up and living in our demented society.

L4LM: What do you recall most about the Ramones in person?

JM: The Ramones are so terrific in the film. They not only are fabulous musicians, but they’re also very funny. I was an extra in the scene when we filmed twelve to fourteen hours of them playing at the Rainbow night club on the Sunset Strip for the concert footage, which runs twenty-two minutes in the film. That was a wild and crazy experience. And during the scenes shot at the high school, when I played a schoolboard member, I would hang out between takes in the principal’s office with the Ramones. They were watching soap operas on a little black-and-white portable TV. I was reading William Manchester’s biography of General Douglas MacArthur. We didn’t say much except to exchange friendly hellos. They were nice but not very verbal.

L4LM: I love the line when Joey Ramone asks for food. “Pizza, I want some!” The manager gives him alfalfa sprouts and wheat germ.

JM: Joey did look rather anorexic. As far as the Ramones’ acting, Allan had the sense to build around their limitations. He assumed they were going to be like The Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night, but they weren’t. It wasn’t like having John Lennon being so witty with wonderful quips. So Allan let the Ramones be themselves, and it’s hilarious to watch and listen to them. I love the elated way Joey exclaims the film’s title when Riff hands him the song she’s written. He also calls Mr. Magree (the music teacher played by Paul Bartel) “Mr. McGloop.”

L4LM: Rock ‘n’ Roll High School stands as a midnight classic. Looking back, do you find yourself as proud of your work?

McBride: The film is the product of many diverse talents working together at high energy, and it is one of those unlikely classics that emerged from all the different elements meshing perfectly at the right place and time. The Ramones have achieved immortality. They are loved and remembered by their fans. I liked them from the beginning because they reminded me of the early days of rock ’n’ roll, when you had simple but clever lyrics and a strong beat you could dance to, as Dick Clark used to say.

I was into rock from the week after it emerged in 1955. They reminded me of Bill Haley & His Comets and Chuck Berry and those other wonderful groundbreaking musicians. The film keeps coming out in new DVD and Blu-ray editions and has been restored beautifully, although one line is missing. After Tom first talks to Riff, he mutters to himself, “I need to get laid.” That line was cut for a TV version and evidently has been lost. Too bad. The three mainstream TV networks wouldn’t play the film unless we changed the ending, and Allan, to his credit, refused. It finally became the first complete feature to play on MTV.

L4LM: Were there any other challenges with the shoot of the film?

JM: Well, we had only twenty-three days to shoot the entire film, an almost impossibly tight schedule for a musical, but that was what was imposed by Roger Corman. Allan Arkush collapsed while shooting the title musical number and had to be taken to the hospital. Joe Dante had to finish the directing and did the postproduction along with Paul Bartel while Allan recuperated. Fortunately, Allan has gone on to a long and successful career as a TV director.

L4LM: Are there any particular scenes that made you laugh the hardest?

McBride: I like the paper airplane that sails long-distance around corners, in and out of the school building, to deliver a message right into the teacher’s ear. That’s “Ear Mail.” Jon Davison directed that ingenious second-unit scene.

But my favorite scenes are the ending and the fantasy scenes of the kids going wild in the school, which are pretty much right from my script. I love the moment when the cafeteria ladies are tied up and having their lousy food thrown at them (“No, not the Tuesday Surprise!”). All that was part of my revenge for having my ass whipped and being brainwashed and fed garbage in high school. One reason I became ill was that I couldn’t stomach the cafeteria food, so I’d sneak out every day to a fast-food joint. And the moment I realized I had bonded emotionally with the Ramones was when I read an interview they did with Rolling Stone about their high school years in Queens. They said that because they were so geeky, the “nice” girls wouldn’t go out with them, so they would sneak into the grounds of the local mental hospital and date schizophrenic girls. They are my kind of guys.

L4LM: Looking back on your high school experience and your breakdown, what qualities in your girlfriend, Kathy Wolf, helped you, and in what ways? Your portrait painted a complex person that the reader could not help but become invested in.

JM: Kathy was so disaffected, so torn and battered by life and by her emotional conflicts over her identity, that she was deeply rebellious. She didn’t buy any of the conventional social wisdom or bullshit. She was sarcastic and funny and sophisticated. Her wit could be biting, but I needed that directed at me at the time, because I was taking everything too seriously. She also was warm and giving emotionally — on her good days. There were times when she was cold and distant, because of her illness, and she was self-destructive. She could be vexing, and she could be adorable. We had a lot of fun talking and making out and laughing about life. That brought me alive after years of repression. She taught me how to live, even though she herself could not survive in this world. I owe everything to her.

See the article at LiveForLiveMusic.com

****

The Broken Places is Joseph McBride’s eighteenth book. He started writing his first book, High and Inside: An A-to-Z Guide to the Language of Baseball, which still in high school. His other books include biographies of Frank Capra, John Ford, and Steven Spielberg; three books on Orson Welles; Writing in PIctures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless; and Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit. McBride lives in Berkeley and is a professor of Cinema at San Francisco State University, where he has been teaching since 2002.

He was a film and television writer for eighteen years and wrote five American Film Institute Life Achievement Award tributes for CBS-TV; one of those specials, The American Film Institute Salute to John Huston (1983), brought him a Writers Guild of America award. He has been nominated for four other WGA awards and two Emmy awards, and he received a Canadian Film Awards nomination for the wrestling drama Blood and Guts (1978). The Broken Places is available in paperback and Kindle editions from Amazon.